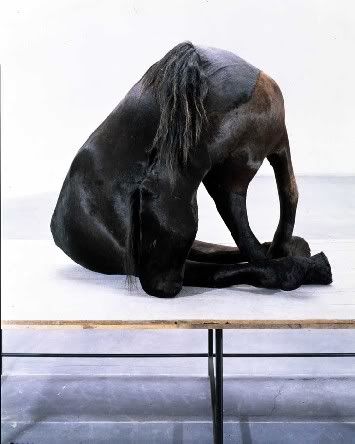

I discovered this artist - Berlinde de Bruyckere - this morning and I had to share images seeing that I have some common interests.

materials used for these pieces are: horseskin, polyester, wood, metal, polyvinyl, resin

materials used for these pieces are: horseskin, polyester, wood, metal, polyvinyl, resin

10 Comments:

you can lead a horse to water but you can shoot, skin, stuff, and pose him in a creative way AND get paid for it....wait never mind.

Great blog. Will bookmark it and return frequently to keep abreast of things I should know about when I make occasional returns to the Detroit area.

That is very effective in that I like that I feel like I need to scrub my eyes out with soap and just general weebie-jeebies after looking at these (and more, thanks for the link) images. And that I need to send a link to your blog to my very best friend who is a photographer/poet but also owns a horse farm so that she can balk and have a predictible reaction and I can feel omniscient.

Long, but informative (from today's paper):

Back from the dead

Not since the Victorians has taxidermy been so fashionable. The way things are going, no trendy wine bar or loft apartment will be complete without a stuffed poodle or horse. But why did dead animals stop being tacky? And what does it mean for endangered species? Patrick Barkham meets the men and women making corpses into art

Emily Mayer's studio is not for the squeamish, especially squeamish dog-lovers. Inside the former workhouse hospital, three very alive Jack Russell-chihuahua crosses gambol among an ark of deceased relatives. Rosie the border collie reclines on a purple sofa. Bertha the foxhound lies, paws crossed, on a workbench. A fox is curled inside a suitcase. Finally, there is The Dog's Bollocks, a taxidermied rat that Mayer believes is her most perfectly recreated rodent yet. He is rolling a jar containing a pair of canine testicles. They came from her neighbour's randy dog, who got the chop.

When not turning strong stomachs, taxidermy has long aroused strong emotions. For many, a childhood fascination for the glassy-eyed inhabitants of the Natural History Museum ends when teenage indignation at the abuse of animals kicks in. For generations, the art of preserving dead creatures has been considered at worst barbaric and at best a relic of 19th-century colonialism.

Now, however, a new breed of artists and collectors are discovering taxidermy. A manky hoof or a moth-eaten fox head that once adorned your granny's spare room is probably propped on the wall of an expensive restaurant. A new shop selling taxidermy is opening next year in London's achingly fashionable Shoreditch. Kate Moss has just spent several thousand pounds on a piece of taxidermy sculpture - a dead bluetit on a prayer book - by the east London-based artist Polly Morgan. Mayer, an artist and taxidermist who has quietly worked in south Norfolk for a decade, has A-list clients including restaurateur Marco Pierre White and artist Damien Hirst, with whom she has collaborated on a number of works. Taxidermy is also returning to the mainstream: ordinary punters are buying antiques on eBay and at auctions, while a new novel endorsed by Richard & Judy's bookclub - The Conjurer's Bird by Martin Davies - has for a hero a character who once would have been considered an outcast: a taxidermist.

Until this renaissance, taxidermy was usually associated with the Victorians and their thirst to discover and classify the natural world. Species found by Captain James Cook in the 18th century were taxidermied and brought home, but until collectors discovered the preservative properties of arsenic, few early specimens survived. (The earliest known surviving example is the Duchess of Richmond's African grey parrot, which died in 1702 and is still perched in Westminster Abbey.) Charles Darwin was a taxidermist and, by the 1890s, cities such as Birmingham boasted 18 taxidermy firms. Most genteel mantelpieces - even in urban areas - were adorned with trophies bagged from the empire - or the local copse.

"They were a reminder of nice things in nature beyond the grimy cities," says Dr Pat Morris, the man who authenticated the Duchess of Richmond's parrot. "They were like three-dimensional pictures in people's drawing rooms. Then the real decline took place in the 1950s and 1960s when it became less socially acceptable. There were other things to do with animals rather than shooting them, such as filming and photographing them. And the animals were getting scarcer and scarcer."

Furry and feathered exotica remained beyond the pale for decades. Now, as antique specimens and pieces of modern art, dead beasts are creeping back into living rooms. "That stigma that went with stuffed animals has gone. People have lost that 'Urrgh, do I really want a dead animal in my living room?' says John Baddeley of Bonham's auctioneers. "There is also a re-emergence of people who want to buy them because they are a work of art and fit into a particular Victorian interior style." Prices are spiralling. Tatty birds that have sat stolidly through a 100-year afterlife inside a glass case are fetching three times their guide prices at provincial auctions. A private collection of 150 birds including a number by the acclaimed Norwich-based taxidermist Thomas Edward Gunn (1844-1922) was sold at an auction in Diss, Norfolk, last month. A (now endangered) bittern fetched £950 (compared with an estimated price of £260-£300), while an avocet, expected to sell for £60-£90, went for £620.

The boom in new taxidermy, meanwhile, is happening despite a number of myths. "People still say 'How many animals do you kill a week?'" says Mayer. "They have no idea that the number of animals who die naturally more than cover the work we do." The laws that govern taxidermy in the UK are strict. Every specimen created after 1947 requires paperwork documenting its history and cause of death. It is legal to pick up most animal and bird species that have died naturally in the UK although there is a list of banned - rare - species. "By far the overwhelming majority of taxidermists came into the profession through a genuine love of wildlife," says Katrina Cook of the Natural History Museum.

Nor is taxidermy simply "stuffing animals". The word itself means "to arrange skin". "A good taxidermist is a sculptor, artist and naturalist rolled into one," says Cook. A taxidermist measures the carcass from all angles, notes eye colour and other soft parts, removes the skin, sculpts a model of the body (balsawood and wire for small birds; fibreglass or foam for larger specimens) and sews the skin back on. Anatomical knowledge and a feel for your animal-on-the-move is essential. "There's a lot of fieldwork involved," says Duncan Ferguson, general secretary of the Guild of Taxidermists. "Although nine times out of 10, the animal tells you what position it goes into."

"In America, most taxidermists come from the hunting, shooting and fishing fraternity. In this country, they don't," says Mayer, a singular individual who pinned desiccated rabbits to her bedroom wall as a child. An increasing number of contemporary taxidermists are artists. Maurizio Cattelan, who is based in the US, is famous for sculptures such as The Ballad of Trotsky, a horse suspended from the ceiling. Hirst himself tried and failed to buy all 6,000 pieces of taxidermy in Walter Potter's Museum of Curiosities in Cornwall when the collection was auctioned off in 2003. The witty and macabre Potter was famous in Victorian times for his anthropomorphised work - tableaus typically showing squirrels playing cards, a kittens' wedding party and rats rescuing each other from a trap. Mayer does not approve of anthropomorphism but enjoys a similarly playful use of her skills (a novelty beard made from 12 white mice - shown on G2's cover- and a piglet handbag) but has focused on developing a laborious process called erosion moulding. Many traditional taxidermists don't believe it is proper taxidermy but it bestows an astonishing lifelike sheen on the dead. And it is more durable than orthodox taxidermy. Mayer can take Rosie the collie into the shower to wash her fur.

Demand for taxidermy may be soaring, but the number of taxidermists is falling. Taxidermists are worried about the lack of young people in the craft. The salary - about £15,000 in museums - is not tempting. "If no kids want to do it, taxidermy is not going to survive," says Mayer. Twenty years ago, the Guild of Taxidermy had 320 members. Now it has 200. Of these, about 10 work in museums and 30 are full-time commercial taxidermists. The rest are part-time (although Ferguson estimates that there may be some 2,000 other hobbyist taxidermists). Many museums, according to Dr Morris, seem to be afraid to support taxidermy because it is politically incorrect. "There is a suspicion that museums are frightened of offending people," he says. Cook, who works to preserve the Natural History Museum's bird collection, argues that taxidermy remains crucial in science and education. "Preserving the skin of an animal is vital to the study of natural history. It has enabled us to identify and describe specimens for science and keep what we call 'type specimens'. Taxidermy is sadly all we have left of extinct species such as the Great Auk or Passenger Pigeon."

One new taxidermist is artist Polly Morgan. The contents of her freezer are not what you would expect of a well-spoken 26-year-old. Wrapped in Sainsbury's bags are a large weasel (with frosted whiskers), a robin, a huge grey squirrel from London, a bat, two white rabbits, a rat, a guinea pig, a chubby wood pigeon, a bag of mice and a tiny quail chick. "I didn't think I could learn because you don't normally meet taxidermists," she says. "And you tend to think of it being archaic or a byproduct of hunting, and I'm not into hunting." Morgan grew up in the countryside, surrounded by animals. Now her mum and a local vet keep her supplied with roadkill and deceased pets. "I get calls from people I've only met once at a party saying their cat brought something in and did I want it. I will drive for miles to collect something, although I'm getting a bit sick of squirrels and pigeons."

Both Morgan and Mayer like to exhibit art that, unlike traditional taxidermy, makes no pretence to be alive. "Taxidermists are really quite purist. They like to pretend death doesn't happen and they are resurrecting animals," says Mayer. "By portraying an animal as dead you get much closer to the truth and it is more disturbing for people to look at. I'm not interested in making pieces of work where people aren't challenged." Morgan, too, likes making "dead" sculptures. "Birds have such a good posture when they die - on their backs with their head on one side. It creates a heart shape. Their wings open and I find something quite touching about how they look - peaceful but vulnerable at the same time." Rather than naturalistic settings, she might curl a rat into a wine glass. One such piece, which looked like a bizarre sorbet, fetched £2,200. She currently has pieces showing at Laz Inc gallery in London and at Studeley Castle in Gloucestershire.

Might the return of taxidermy pose a threat to endangered species? Six years ago, a taxidermist from north London who illegally sold a virtual zoo of endangered species, including two stuffed tiger cubs less than a week old (killed before their eyes opened), was sentenced to six months in prison. Robert Sclare pleaded guilty to 29 counts of forgery relating to applications to trade. After serving his time, he returned and reopened his business, Get Stuffed. The shop, described after the trial by animal rights campaigners as "an animal shop of horrors" continues to trade today.

According to Andy Fisher, head of the Metropolitan Wildlife Crime Unit, there have been no big seizures of illegal taxidermy in the UK since Get Stuffed was raided, although the unit has confiscated illegal taxidermy from elsewhere, including rare birds and sea turtles. Growing interest in taxidermy is not yet reflected in seizures of banned items. "We do monitor various internet sites. If there was a resurgence in rare species then we would be concerned but I think the majority of things being sold are fairly old or are not banned species. It is something we're keeping an eye on." David Cowdrey of the WWF praises the Guild of Taxidermists for fighting wildlife crime and says there is an excellent relationship between many taxidermists and those tackling the trade in illegally killed animals. Most of the problems tend to come from foreign specimens. He urges people not to buy taxidermy from abroad and report any suspicions to the WWF. Cook, meanwhile, advises buyers to beware of buying items said to be antique but without the proof.

Fashions are cyclical and the sudden appearance of taxidermy in interior design is an obvious reaction to minimalism, just as that was, in the words of Cook, "a reaction against the antiquated picture of the dusty Victorian drawing room complete with aspidistra and elephant's foot umbrella stand". But part of the resurgence of interest in taxidermy may also be, as Cook puts it, an aesthetic pleasure. She found with taxidermy she could "make a beautiful thing last forever". Mayer admits it can feel "like cutting your mother up" when you make the first incision in a much-loved pet. "I've got a lot of respect for animals, which is why I don't anthropomorphise them. If you are going to mess around with animals you should give them the best possible afterlife."

Great coda to conceptual art. Of course it would go out silently.

"If you are going to mess around with animals you should give them the best possible afterlife."

'nuff said

jef: I love the article you posted. But which one is "today's paper"? And who is the author?

METRO TIMES REVIEW OF HUMOR SHOW

http://www.metrotimes.com/editorial/story.asp?id=9524

ROBERT SCLARE, TAXIDERMIST JAILED.

First of all, here are 2 "cute" tigers. Please click on each blue hyperlink within the following page link to view the videos. This is what ROBERT SCLARE, the taxidermist in London who was jailed for buying "to order" stuffed endangered species, has in his retail shop "Get Stuffed" (still trading today, unbelievably).

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/article2327856.ece

If you do chance upon this taxidermy horror (human, or not??) at the shop "Get Stuffed" in Islington, North London. If you have a penchant for the smell of death and rot, you need help.

great stuff!

Post a Comment

<< Home